Images for Linwood 1.11.25

For Linwood Scribes 1.11.25:

Linwood Writing Group, Nod Ghosh, Sat 1.11.25

Ideas for Writing – Past and Present

Introductory Exercises

Pick a word from the box and use it in a sentence revealing something about your writing.

Where do writing ideas come from?

Overheard conversations

The news

The past – personal and historical

Prompts e.g.: flash nano starts today https://nancystohlman.com/flashnano/

Other sources?

Sources for historical writing:

Interviewing family members

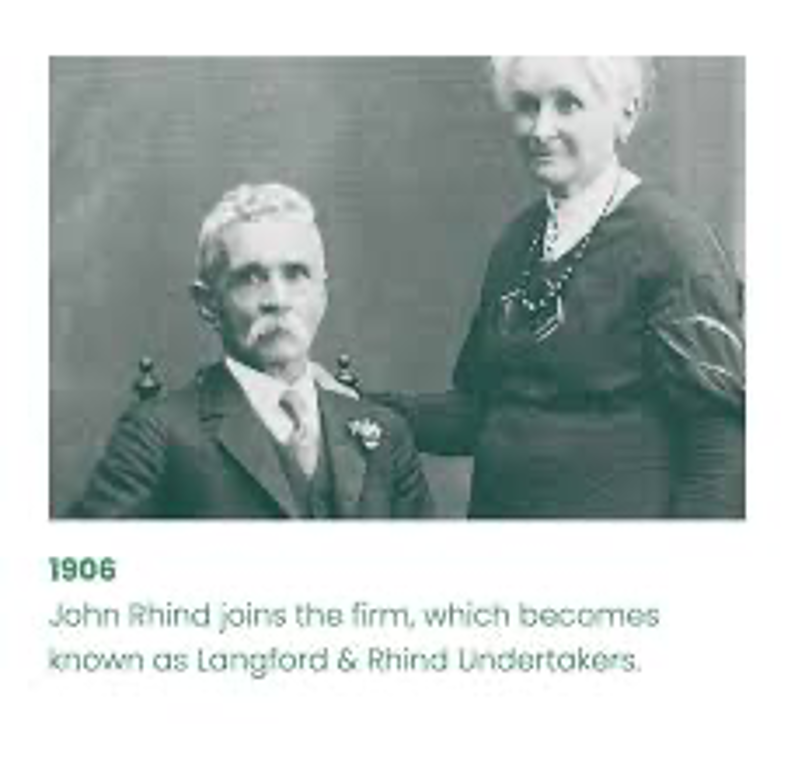

Graveyard visits

Papers Past: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

Shipping manifests

Subscribe to genealogy sites, court records etc.

Museums

Libraries

Saige England, author of “The Seasonwife” states anything set 35 years ago or earlier constitutes historical writing. Whatever your age, use the rich resources from your own life history (diaries, travel notes, concert tickets, magazines, photographs, recipes).

If you haven’t lived through the “historical times” you want to write about, explore the past via books/websites/films/documentaries, which can provide a rich source of information.

Focal points for historical writing

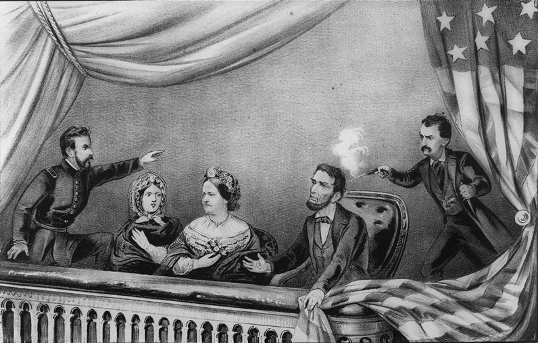

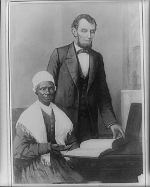

It’s less daunting if you select a time and place to set your work and focus your research accordingly. The era might be associated with a particular historical event or practice, e.g.: Partition of India and Pakistan, abolition of slavery in the USA. (Series of linked pieces.)

See the world through the eyes of someone from that period. What was it like to exist with those people’s limitations and resources? Consider language, healthcare, family sizes, infant mortality, food, fuel sources, lighting, animal husbandry, class, disposable income, clothing, religion, commonly held prejudices, etc.

Any other ideas?

Immersion into a Setting

The Coal Thieves by Frankie McMillan (Shortlisted, Edinburgh Flash Fiction Award 2024)

(The piece was inspired by an image like one on the sheet of pictures)

We whistle like men as we push the wheelbarrows, and those without barrows sling a burlap sack over their shoulder and away we go hauling ourselves up the slag heap and as the soot thickens, blackens our moving shapes – watch out, one of us cries, wary how the slag can suddenly shift, swallow whole a woman with a barrow – while another grunts as she lifts a lump of coal closer to her eyes, places it in the wheelbarrow, as tender as any baby.

We whistle like men until our throats are clagged with soot, our necks bridled by the strain, our faces lost in the black until one of us slips as she sorts through the breakers and we scramble blindly towards her, haul her up, put her hands to the barrow, the fire will burn tonight we say, or don’t say, but it’s there in our eyes and then straight down we come from the slag heap, calling out to each other, pushing the heavy coal, the creaky wheels a lullaby of sorts.

We whistle like men when we hear the patrol, the company police who take our sacks, break our barrows, send us running, but mostly on the way home, our backs aching, our eyes streaming, the only whistling we do is the noise between our teeth, the crooning noise of old women coming home in the dark, fondling a lump of coal in each pocket.

***

Frankie says: the ‘we’ p.o.v. (as used) in “The Coal Thieves” can be a useful device when depicting people in moments of history.

Ekphrastic writing exercise (six minutes, see reference images)

Write a piece in response to a chosen image. You can select a word from the box if you want to impose a further constraint.

Constraints

These can be useful when writing. For example, examine different poetic forms.

The trenta-sei poem https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-poetry/trenta-sei-poetic-forms is a form created by the poet John Ciardi comprising 36 lines that has a particular pattern:

Six sestets (or 6-line stanzas).

Each sestet has the following rhyme pattern: ababcc

Each line in the first stanza makes the first line in its corresponding stanza.

Homework Even if you don’t “do” poetry, try this. Working in different genres can inform and improve our practice. If the form doesn’t appeal, look up definitions for other poetic forms and try those. Examples include: acrostic, Burns stanza/Habbie, clerihew, ghazal, golden shovel, haiku, haibun, pantoum, rengay, sestina, sonnet, tanka, villanelle

Seeking Connections/Thematic Writing

Papal Exercise (Five minutes)

Pick one of the excerpts from the news items below, and write a piece derived from it. Your protagonist could be one of the central characters or a distant observer.

Female Pope

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pope_Joan

Pope Joan (Latin: Ioannes Anglicus; 855–857) is a woman who purportedly reigned as popess (female pope) for two years during the Middle Ages. Her story first appeared in chronicles in the 13th century and subsequently spread throughout Europe. The story was widely believed for centuries, but most modern scholars regard it as fictional.

Most versions of her story describe her as a talented and learned woman who disguised herself as a man, often at the behest of a lover. In the most common accounts, owing to her abilities she rose through the church hierarchy and was eventually elected pope. Her sex was revealed when she gave birth during a procession.

Peace Event at Colosseum

https://anewz.tv/world/world-news/14737/pope-leo-joins-peace-event-with-other-faith-leaders-at-rome/news

Pope Leo joined hundreds of faith leaders at Rome’s Colosseum on Tuesday (October 28) for a multi-faith prayer for peace, urging the world to reject the “abuse of power” and bring an end to wars that continue to claim countless lives. . . Drone footage captured the illuminated square filled with people standing in silence as the candles flickered, representing a collective call to end conflict and foster unity among nations and faiths.

A Pontifical Pageant in 1880

Press, Volume XXXV, Issue 4847, 16 February 1881, Page 3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP18810216.2.23

The “Times” correspondent at Rome sends the following letter dated December 16th 1880.

In the Public Consistory this morning . . .Leo XIII has resumed all the ancient pomp and usage. Even the reports of the proceedings published by the Vatican organs are once again printed according to old fashion, and the heading “Provvista di Chiese,” adopted since 1870, has given place to the official form “Atti del Conciatoro, tenuto dalla Santita di Nostro Signore Papa Leone XIII (tredici) nel Palazzo Apostolico Vaticano il di 16 (sedici) Decembre 1880 (diciotto ottanta).” At ten o’clock this morning, attired in the full dress Pontifical etiquette requires I alighted at the bronze gates of the Vatican, and was entering frankly, as usual, where I am well known and, I may justly say, well received, when the sergeant of the Swiss Guards drew up his cane horizontally, barred my passage, and demanded where I was going. “Into the Consistory,” I replied. “Where is your biglietto?” he asked. “Biglietto?” I rejoined. “Si, Signore, il biglietto: without the biglietto I cannot let you pass.”

Closing a Gap

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cnve5mdze8yo

King Charles and Pope Leo made history in the Sistine Chapel by praying side by side – a first for the leaders of the Church of England and Catholic Church.

Under the scrutinising eyes of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, when Pope Leo said “let us pray”, it meant everyone, including the King, closing a gap that stretched back to the Reformation in the 16th Century.

Spending a Penny at St Peter’s Basilica

https://www.stuff.co.nz/world-news/360852720/pope-leo-shocked-after-man-urinates-altar-during-holy-mass-vatican-city

Pope Leo XIV is reportedly “shocked” after footage emerged of a man urinating on an altar during Holy Mass at the Vatican City on Friday (local time).

The video showed a man at the top of the Altar of Confession at St Peter’s Basilica – in a spot where the sitting pope typically performs mass. He was then seen dropping his pants to his ankles and beginning to urinate.

The man was quickly taken away by plain-clothed police, but not before mooning worshippers as he pulled his pants back up.

Homework Write pieces in response to each article you didn’t use, to make a collection of pieces linked by a common theme. Find more Papal stories if you want to expand the collection.

Prompt word exercise (Six minutes)

Write a piece that incorporates the following words:

Castle, steam, vestement, torrent, horse, log, scorpion, timepiece, garden, toil

For NZSA Children’s Literature Hub 26.10.25

NZSA Children’s Literary Hub

How to Bake a Book (Everytime Press), by Nod Ghosh

Sunday 26th October 2025 Handout

What we will cover:

Introduction with exercise

Why I’m here

Learning the basics

Genesis of “How to Bake a Book”, with a reading

Thoughts on writing for children

Taonga exercise

Answers to commonly asked questions

How do you find time to write?

The Publishing process.

The Importance of Play.

Exercises from the back of the book, if time

Introductory game

• Take two sheets of paper

• Write something commonly regarded as negative on one sheet, e.g.: anger, bomb, spider, vomit

• Write something typically thought of as positive on the other, e.g.: chocolate, compassion, shelter, birthday

• Fold both sheets so the writing is concealed, marking the negative one with a minus sign, and the positive with a plus

• Place the negative one in the negative foil box, and positive one in the positive box

• Pick one of each, (hopefully you don’t get your own, but if you do, work with it)

• Write an introductory sentence or two about yourself, incorporating the “good” and the “bad” word.

(You are allowed to lie!)

Thoughts on writing for children

• Every human in existence was once a child.

• Remember that.

• Look at the world through your child-eyes.

• Though they are all of the same species, there are many different sorts of children.

• Some variations can be catered for: books for newborns are different from those for older teenagers.

• Learn about what has already been done. Visit libraries, bookshops, people who have or care for children.

• How do they handle layout, language, literacy requirements?

• Other aspects of the child are highly individualised.

• Your character(s) can’t represent everyone, but they can appeal to a wide group if you give it some thought.

• To quote Ben Brown: “The mantra is that boys don’t read. It’s not that boys don’t read. It’s that you’re giving boys shit that they don’t want to read.”

In 2021, Ben became the first Te awhi rito Reading ambassador.

(See Ben at Common Ground, Commoners Bar, at Sherpa Kai, Lyttelton 7pm tonight.)

• If you “preach” morals or lessons, don’t be surprised if children don’t want to know.

• Be subtle when imparting wisdom or information!

• Learn how to craft the style you aspire to write.

• For example, if writing in rhyming verse, appreciate it is easy to do, but very hard to do well. Read the masters: e.g.: Lynley Dodd.

• Learn about scansion, appreciate where syllables are stressed, test out the rhythm.

• Don’t invert sentence structure to force a rhyme. It helps to choose the final rhyme word of a pair/group first, and select rhyming words to appear before it.

• Writing songs or poetry can inform you of the skills required.

Taonga Exercise (Five minutes):

Select an item from the “taonga tray”. Write a piece inspired by emotions the item triggers in you. Don’t over-think it.

Things you might want to incorporate:

Where did it come from?

Imagine the item is much larger than it is in real life.

If the article could make a sound, what would it be?

What if it were sentient?

Answers to commonly asked questions:

How do you find time to write?

Exercise from the end of the prologue. (Do this when you get home)

Ten Minutes When You Must Write

You want to write, but you’re too busy to start. If that’s you, do this exercise now. If you won’t do it now, set your alarm ten minutes early tomorrow morning and do it then.

Ingredients

• something to write with

• something to time ten minutes with

Method

• Preparation required: none

• Write for ten minutes without stopping

It doesn’t matter what you write about.

It doesn’t matter if you don’t feel inspired.

It doesn’t matter if you haven’t had the “big idea” yet.

It doesn’t matter if what you write is bollocks.

Have ten minutes passed yet?

No

Keep going

Have ten minutes passed yet?

Yes

Stop

***

The publishing process

Chapter Nine “Getting Your Work Out There” focusses on what to do after you get your work to a publishable standard. Topics covered include: the submission process (online and print, for short and long work), free submissions vs. those who charge a reading fee, using social media to identify places to submit, high calibre publications with low acceptance rates and vice versa, identifying “vanity press”, marketability, remuneration, bios, author websites, CVs, keeping track of submissions, unsolicited submissions, agents, competitions, post-publication promotion.

Chapter Twelve, “Other Ingredients for a Book”, deals with other aspects required for a book beyond writing. You’ll need to be particularly aware of these elements if you choose to self-publish. They include structural editing (story structure, identifying inconsistencies of ideas etc.), copyediting (ensuring text conforms to consistent style, sentence construction etc.), proofreading (correcting any remaining errors).

Synopses. Endorsements. Typesetting. Print-on-demand vs print run.

Distribution. Marketing.

Chapter Fourteen, “Where to Next?”, elaborates on the latter. Plus: seeking reviews, the role of booksellers, book launches, publicity via media.

The Importance of Play

As author for children, you are well aware of how important a playful approach is for children.

But what about you?

The book incorporates “recipes” at the end of each chapter. Some are just activities. You can break your writing time up by dedicating ten minutes here and there towards work / study related activities, household chores . . . People can use minutes less efficiently when they have plenty.

“Stone painting” comes from Chapter Thirteen, “Ancillary Activities”

“Creative Journalling”, is the exercise at end of Chapter Thirteen, p131).

You can use a blank notebook, or an old hardback book. The purpose is to free up the creative process. The exercise talks you through the process, and provides suggestions:

Give yourself permission to deface the book.

• You could paint the cover and add a title.

• Don’t necessarily work from the beginning. Start in the middle or the end.

• Using a fat marker pen, write automatically for the duration of a piece of music. Use two pieces: one you know and love, another you’ve never heard before.

• If you’re using an existing book, highlight selected words to create sentences that are unrelated to the original text.

***

Exercises from the back of the book

We likely won’t get through many of these during the workshop. Take them home and complete at your leisure.

In the book, these all have varying recommended time limits, but we will do them in a shorter time period during the workshop, (3-5 mins) depending on how much time we have left.

Setting Exercise

Recall a room or building from your past – a place you lived or visited or a location seen in a film or on television. Do a rough sketch of a floor map of the place. Where are the doors /windows? Are there any emotions associated with this place? Jot down key words. Create a story in this setting where the main character overhears an argument they’re not supposed to. Evoke senses besides visual (smell, sound, touch, taste).

Elaborate on a scene

Two cars are parked next to each other on the roadside beside a river. A man steps from one and lets two children out of the back. The children walk away from him towards a woman holding the door of the second car open for them. The narrator may be one of the characters or an observer, or you can use an omniscient perspective.

Vandalism

Show your character’s reaction after being told somewhere / something that is important to them has been vandalised / stolen / damaged and can’t be accessed / used anymore. You can use dialogue, but try to show how the person feels without describing their emotions directly. If they do speak, focus on what their voice sounds like as well as their words. How do their stance and mannerisms reveal their feelings? How do other people respond to them?

Hunger Game

Describe what it’s like to be hungry to someone who has never felt hungry.

Emotional Responses

Select one or more of the following, and show the characters’ emotions without spelling them out in a story that takes place at a train station.

• He felt tired.

• She loved him.

• They loathed one another.

• The children were bored.

Sensory Maze

Evoke the senses: sight, sound, touch, taste and smell as your main character finds themselves in a new situation. Perhaps they wake up in hospital, with little idea how they got there. Maybe it’s the first day in a new school or job. Synaesthesia is a condition where stimulation of one sense leads to an automatic experience in a second sensory pathway. You may want to use this concept to enliven your writing.

Memory

Identify one of your earliest memories. Close your eyes and immerse yourself in that zone. Conjure smells, the feel of the air on your skin, and your emotions. Were you happy? Were you anxious? Try to gauge whether it is a genuine memory, a memory of a memory, or an assumption triggered by a photograph from your past. Let you from that time take control of the keyboard or pen, and write about that scene.

Strangers

Write about two characters who don’t know each other, showing how they interact, for example at a party, job interview or on social media.

Animal Magic

Make a story set in your home from the perspective of a non-human animal, large or small. Someone has just died as the story begins.

For NZSA 18.9.25:

How to Bake a Book, by Nod Ghosh (Everytime Press)

NZSA 2025

Write your name on the identity spoons, so we know who you are.

Tell us where you are in your writing journey, by giving a single sentence bio – in third person, as it might appear in a publication.

Taonga Exercise (Five minutes):

Select an item from the "taonga tray". Write a piece that incorporates the item. It could relate to how the item was found or made, or a human interaction with it, e.g.: it features as a gift/is involved in a transaction/is used as a murder weapon etc. Or take a more fantastical approach. Imagine it is much larger, or you are much smaller, and are walking next to or into it.

Frequently Asked Questions

People often ask questions about how to get a book into the world. I aimed to provide the answers to these sorts of questions in “Bake”.

Here are some points discussed in the August 25 NZSA Canterbury meeting:

Layout of Dialogue

Use of attributions or not. There is no set rule regarding “he said/she said”. A publisher might have “house rules” they wish authors to comply with regarding use of single or double quote marks, italics, none at all, or whether a new line is required for a new speaker.

As long as the dialogue is easy to follow, anything goes. This can be achieved either by use of attributions, the use of “beats”, where an action by the speaker is described immediately after they speak, distinctive verbal style or other contextual clues.

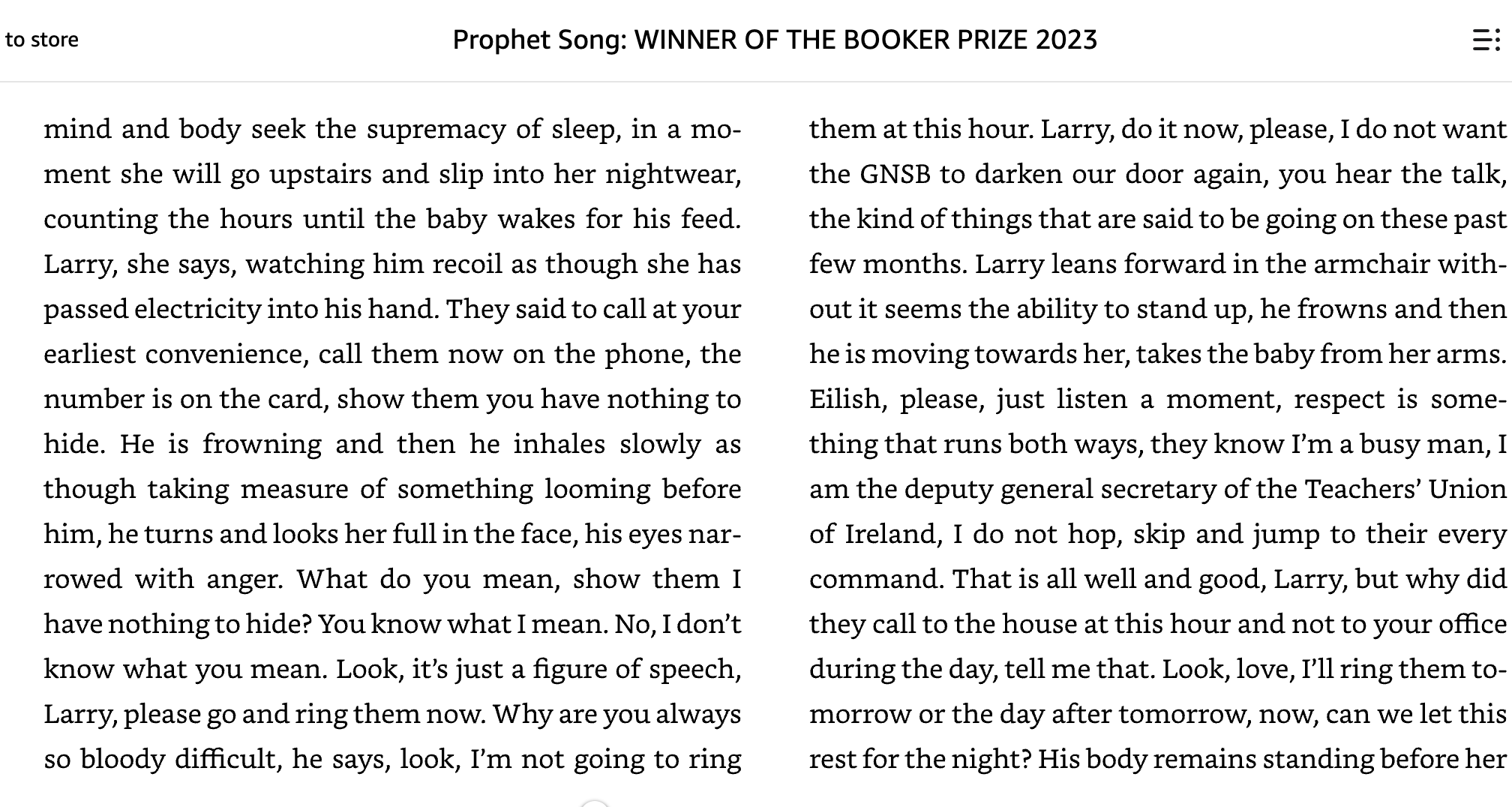

Look at the example that begins “mind and body seek the supremacy of sleep”. This is taken from “Prophet Song” by Irish author Paul Lynch (Booker prize winner 2023). A conversation begins partway down the page at “Larry, she says . . .” See how skilfully the writer allows the reader to keep track of who is speaking.

Who is main protagonist? (Point of View)

There’s something about POV in Chapter Six of the book, “Sets & Drugs & Rock & Roll & Shady Characters”: When a minor character is given a point of view, i.e., the narrative comes from their perspective, whether that is in first or third or even second person, they cross a line and can be considered a protagonist.

There’s more on POV in Chapter Three, “Word Choices”: Is your work written in first,

second or third person? If third, is it a close third person, which borders on first, or is there more distance? Does only one character’s worldview shape the story?

How important is it to be consistent? You can change perspective, but do so in a considered manner that doesn’t suggest, for example, that the author was carried away and forgot they were writing about a fictional character, not themselves. Typically, a POV shift takes place between chapters or paragraphs.

Omniscient or eye-of-god POV, where multiple characters’ perspectives are prominent were more common in the past, but have been used successfully in contemporary literature too.

Tense

Also from Chapter Three, “Word Choices: Think about tense. How important is it to consistently use past, present or future narration within a piece? It isn’t, provided the changes enhance rather than appear accidental. For example, changing from past tense to “the dramatic present” can increase the tension of a key event.

Character profiles

This is taken from the exercise at the end of chapter four, “Different Genres” on writing a character study:

How old is the person? What is their relationship to the existing character(s)? Where were they born? Do they have siblings? What do they do for a living? Are they a morning or night person? Do they have any distinguishing physical characteristics or verbal tics? Is there anything they refuse to eat?

This is from Chapter Six, “Sets & Drugs & Rock & Roll & Shady Characters” on keeping character lists (when writing a novel):

What sort of school did the person attend? Did their parents divorce? . . . What is their accent? What is their attitude towards money? Can they drive? Are they ill? Do they tell lies?

These are only examples. Come up with your own list if what you need to “interrogate” when forming a character. Include the “big questions” such as class, political standpoint, religious beliefs. But also consider smaller stuff such as whether they interrupt people, walk in a funny way, what their voice is like or whether they are thrifty.

You could make notes about their physical appearance. While not as important as you might initially think, it’s good to record these in your character profiles to help you describe people consistently.

Timeline, linearity

From the exercise at the end of Chapter Five, “Story Structure”: Write a story plan in two ways, one with a linear timeline, the other non-linear, and then review both plans:

Do any juxtapositions you’ve made in the non-linear timeline add anything to the story? In what way are they better than the linear timeline, if at all?

The exercise is to examine one element of story structure – the timeline. It can be tempting to write non-linear narratives without giving it much thought . . . In its laziest form, you might add a flashback to “explain” something that’s about to happen in the main timeline. This can

come across as a contrived afterthought . . . Flashbacks and flash forwards can be a poignant way of revealing the storyline, aiding character development in an original way. However, it’s wise to craft non-linearity so it adds to the reader’s experience, rather than jumping back and forth because that’s the order in which the ideas come to you.

There’s more in Chapter Six, “Sets & Drugs & Rock & Roll & Shady Characters”:

When you read books or watch film and theatre, observe how time is handled. As well as linear versus non-linear timelines, one character’s timeline may be handled differently from another’s. Consider why these choices have been made.

If you play around with timelines (a necessity if writing about time travel, for instance), keep detailed notes to avoid unplanned conundrums.

Setting

As the name may or may not suggest, Chapter Six, “Sets & Drugs & Rock & Roll & Shady Characters” contains information about setting:

Setting includes time, place, and other elements that provide a base for your narrative. The chapter goes on to outline how it’s better to create the characters’ world as an integral part of the storytelling than to dump too much description at the outset.

There’s discussion about historical writing: use of signposts for the era, technology, language choices and how attitudes such as gender roles are influenced, differences in life expectancy.

When considering location, think about climate and length of daylight.

Incorporate fragrances and odours.

When you describe locations, you can draw on real places you have visited. Use your catalogue of memories. Travel diaries are useful. You can transplant details from one real place to another and invent a new imagined scene. Compared with writers in the past, we have the benefit of online satellite images.

Imagination is an essential tool, especially when you can’t easily access reference material. What does that alien’s skin feel like? How is vision affected when light doesn’t travel in straight lines? Has that corpse been there long enough to reek?

Investigating whether a change will enliven your work, or help you identify what needs developing

This is mentioned in the exercise at the end of Chapter one, “The (Almost) Infinite Freezer”. Ways of seeing work from different perspectives include changing the tense, point of view (first to third person or whatever) or even the font, unless you’ve written longhand. Try reading the work out loud. Try reading the words in a different accent. Put them through Google Translate and convert into a different language. Then translate them back. What has changed?

Use of beta readers

In chapter eleven, “The Writing Community”, I discuss finding well-matched partners for mutual critique. Aim to match your levels of experience and productivity/output/turn-around time. There’s a 2½ page section on how to give critique, and a 1½ page section on how to receive feedback. Both are important.

The publishing process

Chapter Nine “Getting Your Work Out There” focusses on what to do after you get your work to a publishable standard. Topics covered include: the submission process (online and print, for short and long work), free submissions vs. those who charge a reading fee, using social media to identify places to submit, high calibre publications with low acceptance rates and vice versa, identifying “vanity press”, marketability, remuneration, bios, author websites, CVs, keeping track of submissions, unsolicited submissions, agents, competitions, post-publication promotion.

Chapter Twelve, “Other Ingredients for a Book”, deals with other aspects required for a book beyond writing. You’ll need to be particularly aware of these elements if you choose to self-publish. They include structural editing (story structure, identifying inconsistencies of ideas etc.), copyediting (ensuring text conforms to consistent style, sentence construction etc.), proofreading (correcting any remaining errors).

Synopses. Endorsements. Typesetting. Print-on-demand vs print run.

Distribution. Marketing.

Chapter Fourteen, “Where to Next?”, elaborates on the latter. Plus: seeking reviews, the role of booksellers, book launches, publicity via media.

Exercises from the book

(If we don’t have time to complete these, take them home to do later.)

Hunger Game

Describe what it’s like to be hungry to someone who has never felt hungry. (Five minutes)

Automation

Write for t minutes without pausing using a stream of consciousness process where what you’ve written triggers the next part, which may or may not have an identifiable association. It doesn’t have to make sense.

Surreal Past

This exercise is ten minutes long. Recall an event / experience from your early childhood. Write an account of the event / experience, but introduce at least three elements of surrealism into the story. For example, if writing about a scary music teacher, you could include something about the sleeping dragon that lives in the guts of the piano. If writing about a memorable holiday, you could add a part where the narrator (you) flies over a beach once the adults are asleep. Think of something impossible that is compatible with the scene.

Prompt Words

Write for four minutes, including the following prompt words:

heavy, tent, last, tight, order, chaos, thimble, danger, outside, hammer.